On Woman Hating

Project For Empty Space, September 2024

On Woman Hating gathers woman-identifying artists who address various mythological femmes, cultural and religious icons, issues of sexual exploitation and physical abuse, body autonomy, and the inextricable link between femininity and the natural world in their work. It considers the contemporary consequences of societal shifts including a departure from goddess culture - that is a shift to a monotheistic patriarchal faith-based system - the development of “modern science,” and the initial conception of “mankind.” Guided by an eco-feminist politic, On Woman Hating looks at the intersections of race, gender, climate change, reproductive rights, and capitalism to negotiate a path toward centering the divine feminine in our individual and collective activism.

Artists include: Destinie Adélakun, Ania Freer, Misha Japanwala,Utē Petite, Adrienne Tarver, and Victoria Walton.

On Woman Hating Extended Essay by Alyssa Alexander

On Woman Hating gathers woman-identifying artists who address various mythological femmes, cultural and religious icons, issues of sexual exploitation and physical abuse, body autonomy, and the inextricable link between femininity and the natural world in their work. It considers the contemporary consequences of societal shifts including a departure from goddess culture - that is a shift to a monotheistic patriarchal faith-based system - the development of “modern science,” and the initial conception of “mankind.” Guided by an eco-feminist politic, On Woman Hating looks at the intersections of race, gender, climate change, reproductive rights, and capitalism to negotiate a path toward centering the divine feminine in our individual and collective activism.

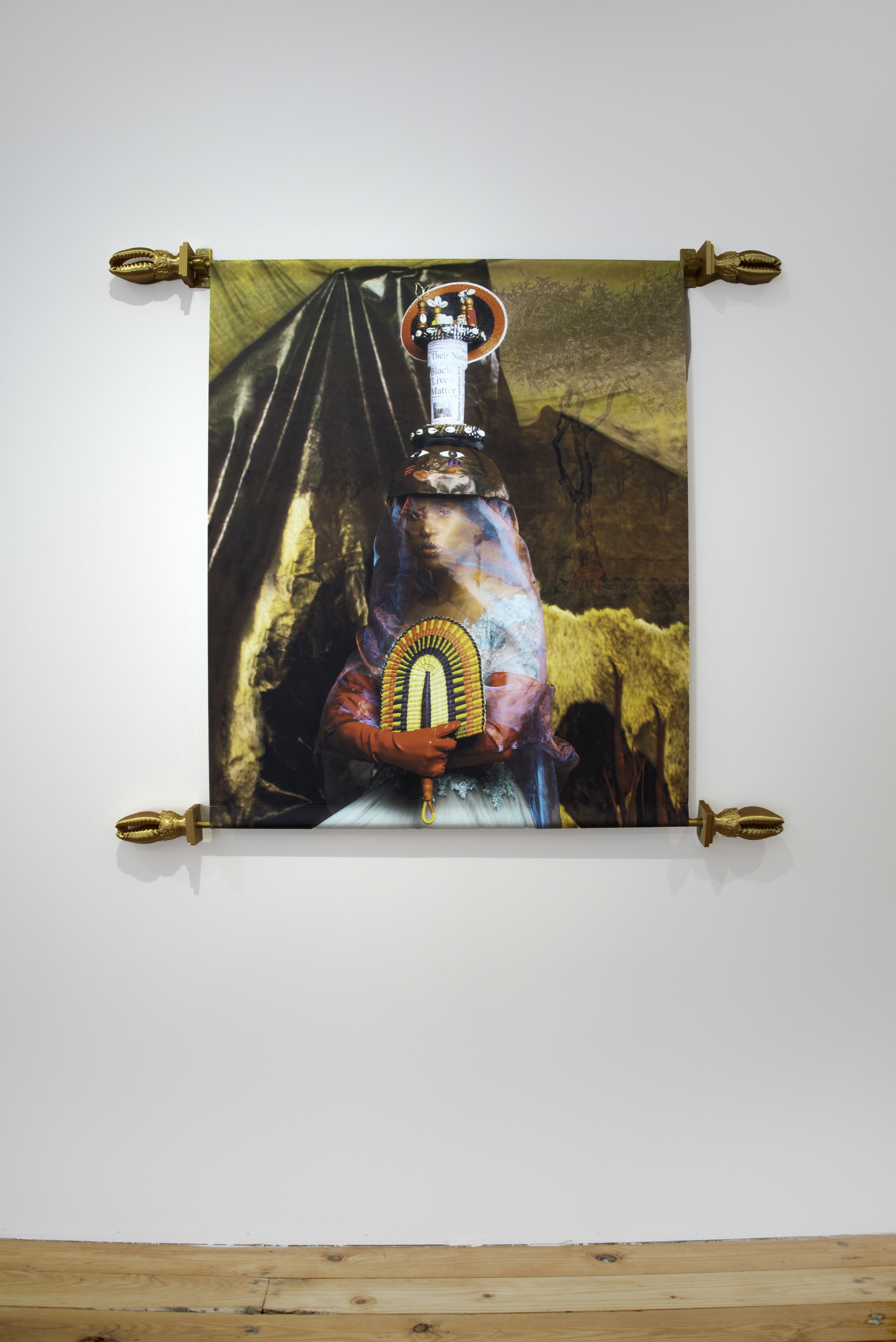

Destinie Adelekun’s Daughters of the Diaspora images orishas, like Yemayá and Oya, from the West-African Yoruba spiritual tradition through intricately staged portrait photography. The series is an exploration into the rich tapestry of Afro-indigenous folklore, delving into the symbolism of women and non-binary individuals within the African diaspora, and tracing the threads of spiritual practices and rituals that existed prior to European occupation and the Middle Passage. The orishas belong to a lineage of feminine and gender-fluid icons across cultures that are as feared as they are revered.

Ania Freer’s films, Shango and Shanny, capture the layered relationships between inhabitants of rural Jamaican villages and ‘riva mumma’ - a Black mermaid figure also known as the river maiden or mami wata in other diasporic cultures. The story of river muma also finds its origins in West Africa, and is brought to the Caribbean via the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The indigenous folklore retained by enslaved Africans, as well as a deep reverence for Yemayá is influenced by the rise of trade and capitalism between shores, and mami wata becomes a symbol of financial prosperity and wealth. What pervades many iterations of mami wata is the fearsomeness of the character, her instability, vanity and unpredictable nature if crossed - a trope that has been replicated for generations in literary and visual media. The subject of Freer’s film Shango speaks to the nuance of a reverent dynamic; one where his care and fastidiousness about the land and riverbed is born of respect not fear. Shango’s work in preserving the land - in service to a woman no less - puts our contemporary relationship with “mother earth” into perspective. What might our world be like if our relationship with the natural world was horizontally aligned rather than vertically/hierarchically? Moreover, how do more representations of love and care in visual media, like Freer’s, benefit the treatment of women at large?

Adrienne Tarver’s canopy of hand painted foliages, In Fertile Shadows, points to the proliferation of the banana crop in the tropics at the time when J.Marion Simms’ inhumane experiments on Black women would earn him the title “father of modern gynecology.” Installed in tandem, Origin: Fictions of Belonging, references the “visible and invisible veils'' of race and otherness, the tropical locales of many colonized non-western people, and the fictions and myths created to support their status as “other.” The themes at play here harken back to the dawn of modern science, the distinctions made between “man” and “nature,” men and women, and racial classification. The perception of both women and non-human species as “wild” has justified their exploitation and subjugation to centuries, earning many men accolades, wealth, and historical notoriety. Tarver’s series Terra Incognita, reframes the “unknown” territories traversed by colonial entities as an Edenic space rife with possibility. Works like The Dreamers and The Watchers “explore the arena of the pre-domestic, the pre-colonial, and the pre-patriarchal, planting the seeds of an alternate, unknown history,” according to Tarver. Similarly, works from Manifesting Paradise pull from tarot and divination practices to visualize futurity.

Utē Petite’s Unseeded Seminal Territory, depicts an unsettling scene of femicide - one that speaks to the violence enacted under systems of power when race, class, and gender “collapse (or are absolved) depending on one's allegiance, commitment, and receptiveness to be used as a tool of empire,” as posited by the artist. Physical harm against women, and trans-women specifically is perhaps the most overt byproduct of woman hating. Domestic violence, sexual assault and abuse are common place not only on the big-screen, in popular music and cinema, but in our interpersonal lives, as close to 30% of women will experience intimate partner or sexual violence or in their lives. The statistics around the murder of Black trans women in the US are equally alarming. As perhaps a counter balance to the pervasiveness of harm, Petit’s art practice centers nourishment. She’s worked tirelessly on rematriating the land of her family and community members in New Orleans – a project that sits at the intersections of visual art, farming, and social practice and firmly in the tradition of Black woman-led grass-roots organizing.

Body casts by Misha Japanwala abstract anonymous femme’s bodies into land-like forms, taking on the shapes of hills, valleys, and cliffs. This gesture of documentation is one that exists outside of the exploitation, dominance, and harm most inflicted on marginalized woman-identifying bodies. The casts, and the casting process, have been a liberative experience for trans and cis-genedered women living in a conservative Pakistan, where shame is often a tool of control. Parallel to the body casts, her Hands of Revolution series are casts of hands of various South Asian individuals who are working across art, journalism and policy to create radical change.

Victoria Walton’s studio practice investigates the myriad ways societal systems “build and break us down simultaneously” through explorations of earthen materials and their connection to the body. In Release, a complex composition of tree roots, soil, hemp rope, and porcelain, the artist plays with the legibility of struggle and the beauty of diversity in the ‘natural’ and manmade worlds. From the artist: “The word “natural” has harmful connotations when it is tied to conventional ideals…It has long been associated with the gender binary, heterosexuals, able-bodied persons, and those who conform to societal standards. This rigid association aims to constrict independent complexities and interpersonal truths outside these lived experiences. Within the disabled community, there is a great desire to reclaim how "natural" is used…The importance and reclamation of nature in my work is a call to a deeper personal and cultural association with the organic beauty around us, but how Black, disabled, and queer and trans people experience these same dynamics and are also part of these frameworks.”

While the links between abortion access and climate change may not be immediately apparent, understanding how ideologies of control, consumption, and conservatism converge to impact policy is paramount. This exhibition is as much about the artists and their individual works and practices as it is a prompt to begin thinking expansively about many of our contemporary issues have foundations in man’s desire to dominate.